Photo by Asher Kaye

Friday, April 11 at 7:30 pm marks a coveted event in the Oberlin Conservatory calendar — the long-awaited performance of Mahler’s Symphony No. 1 by the Oberlin Orchestra. The excitement is palpable among Conservatory students, who are ecstatic to see the work graduate from the throes of seating audition repertoire to a full performance on the Finney Chapel stage. But perhaps the most excited is Sophia-Louise (Sophie) DeLong, who moves one step closer to her dream of musical academia as the author of the performance’s program notes.

I was fortunate to see this excitement for myself, sitting with DeLong in a quaint little coffee shop and getting to learn about her unique position as a performance violinist looking to take the plunge into musicology.

Her approach to music, and the violin, is unconventional compared to her peers, coming from a childhood in fiddle playing and folk music rather than Mozart CDs and Suzuki books. She cites Professor of Musicology Charles Edward McGuire as an important guiding figure in her shift from solely performing to engaging in academic analysis. For the past year, she has been employed with him to expand the Musical Festivals Database, his archive of research on British festival repertoire between 1695 and 1940. It was in one of their weekly meetings that the stars aligned for her opportunity with Mahler.

“My partner wanted to know who was writing the notes, and so I asked. And then McGuire said ‘Why, do you want to do them?’ And I said ‘Yes, I do.’”

While this is not DeLong’s first foray into academic prose on music, this is her first official outing with writing as opposed to performing. When asked about her research process, she described scouring program notes from other performances at major concert halls and flipping through fascinating literature in the library. She also mentioned conductor Raphael Jiménez’s recommendation to read the foreword in the Bärenreiter edition of the score. DeLong unfortunately found it unsatisfying, largely due to one big detail.

“It completely — and I mean completely — ignored his Jewishness,” she said.

This was one of her biggest points in parsing through Mahler and clearly something of deep-rooted importance to her. It permeated our further discussions of both the music itself and the valuable role that program notes have in framing a performance. She attributed part of the current cultural obsession with Mahler as tangentially related to his Jewishness.

“Thanks to people like Leonard Bernstein and Bernard Haitink, that Mahler revival in the 60s really aided in making his music heard again. I made sure to reference that it had only disappeared in the first place because of the banning of Jewish-composed music by the Nazis.”

She described Mahler’s works as “very personal writing” — the music is not only reflecting his emotions, but also his Jewish heritage. This is seen most prominently in the second and third movements of the first symphony.

“There was a Mahler movie,” DeLong said, “which uses the second movement in a way where it’s people dancing with beer mugs in their hands. And that’s what I visualize every time I hear it — it’s also a Ländler, a European folk song and dance that inspired the Viennese waltz.”

The typical choice for a second movement in the symphonic form is this type of waltz, and DeLong noted that Mahler “taking it back to its folky roots [as opposed to the standard Viennese waltz] is a choice. A very distinct difference.”

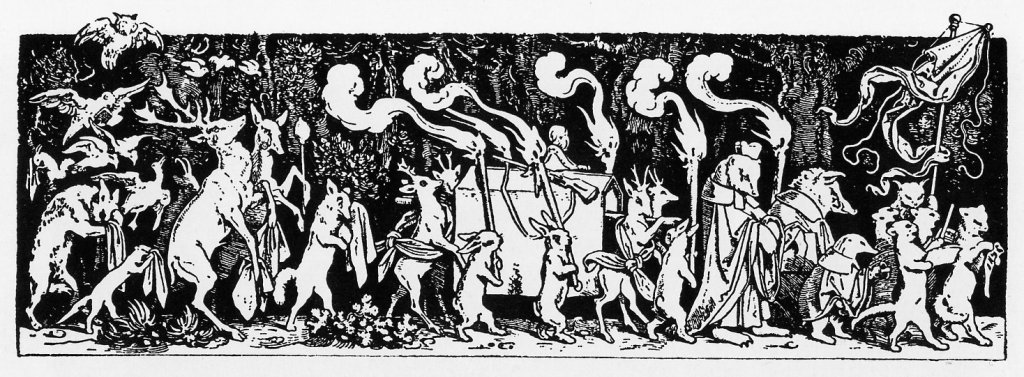

The third movement continues this dedication to cultural heritage, as well as being extremely programmatic. DeLong explained that it was based on the woodcut image titled “How the Animals Bury the Huntsman.” While most have come to recognize the movement for its initial funeral dirge theme — the lullaby “Frère Jacques” set in a minor key — in the second theme, Mahler infuses elements of Bavarian and Jewish street musics. “It’s something Mahler does consistently in his compositions. He makes a point to intentionally include Jewish music. All of that doo-WOOP! That’s all Klezmer.”

DeLong said that Mahler himself was indeed a very intentional person, and a very particular person. “[He] was tyrannical about the way he did things — the way he composed, the way he conducted. He was very specific.”

These specificities include the concert hall rituals that many classical music fans are familiar with today, such as the dimming of house lights and discouragement of clapping between movements. DeLong cited this obsession as a spotlight on the fundamental complexity between Mahler’s Jewishness and his musical role models. “[The concert ritual] is all heavily influenced by [Richard] Wagner, who was known to be anti-Semitic. But Mahler did look up to Wagner.”

I could see DeLong’s passionate empathy for Mahler, as she talked about the struggle he must have felt within himself. “Letting go of the self and your identity while still writing scenes of Jewish folk music and Klezmer. And there is something to understand about Mahler instilling these rules in his concerts. They reflect what he truly believed about music at the time: that any noise could mar the listening experience. And that music itself is sacred.”

Be sure to feel that sanctity and passion for yourself by reading DeLong’s program notes — and seeing her perform in the violin section — at this Friday’s performance of Mahler Symphony No.1!

This article was updated on April 18th, 2025.